NEWS

NEWS

30 Dec 2025

30 Dec 2025

Women in the Workplace 2025: Where Female Leadership Slows

Women in the Workplace 2025: Where Female Leadership Slows

In 2025, the discussion around women’s advancement stayed loud and visible. Yet promotion and leadership representation often do not move in practice. This is exactly what Women in the Workplace 2025, published by McKinsey & Company in partnership with LeanIn.Org, examines.

The report compiles more than a decade of longitudinal data and shows where progress holds, where it stalls, and where it starts to reverse. According to it, only 50% of companies now say that advancing women’s careers is a top priority, down from 65% in 2019. Nearly half of women report lower interest in promotion than earlier in their careers. That’s even when performance ratings match or exceed those of male peers.

At Drofa Comms, we observe the same patterns in finance and technology. These sectors operate with tighter risk tolerance and stronger internal gatekeeping. Promotion windows can be narrow, while endorsement can outweigh effort. This is also where communications becomes part of the operating system. Visibility is built through staffing, access to decision-makers, and the narrative carried into calibration.

We treat this report as a baseline. Below, let’s unpack the key findings through a practical lens on visibility and women’s leadership in 2026.

The Leadership Pipeline Gap and What’s Driving It

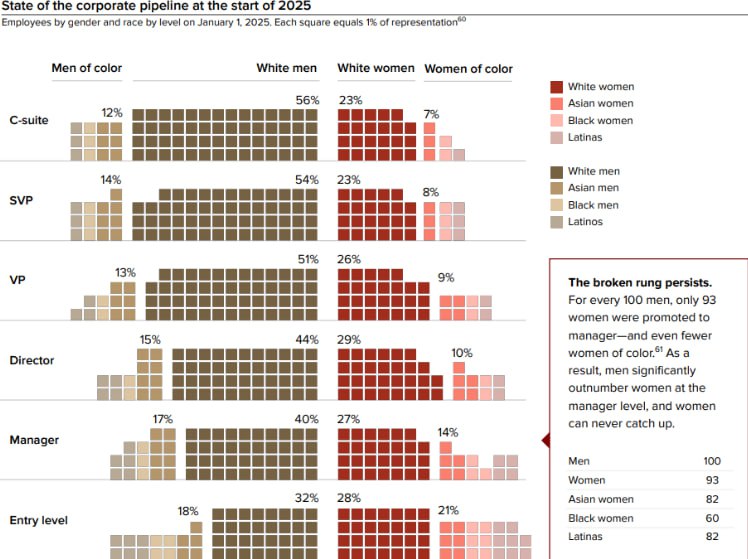

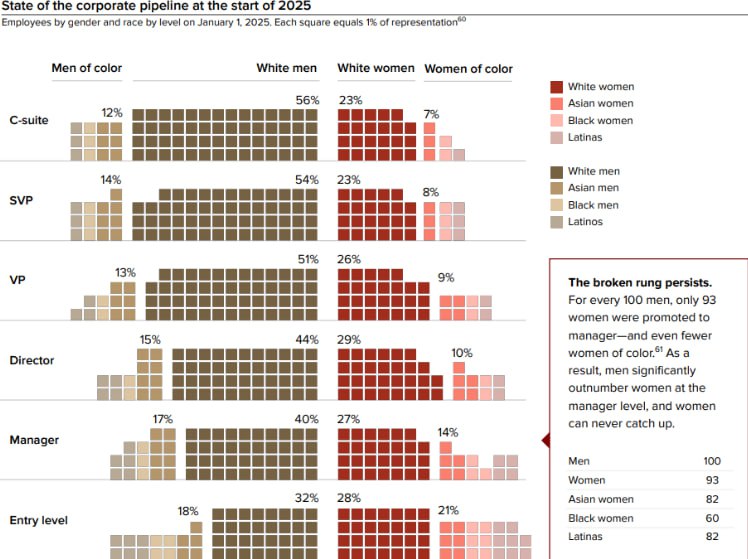

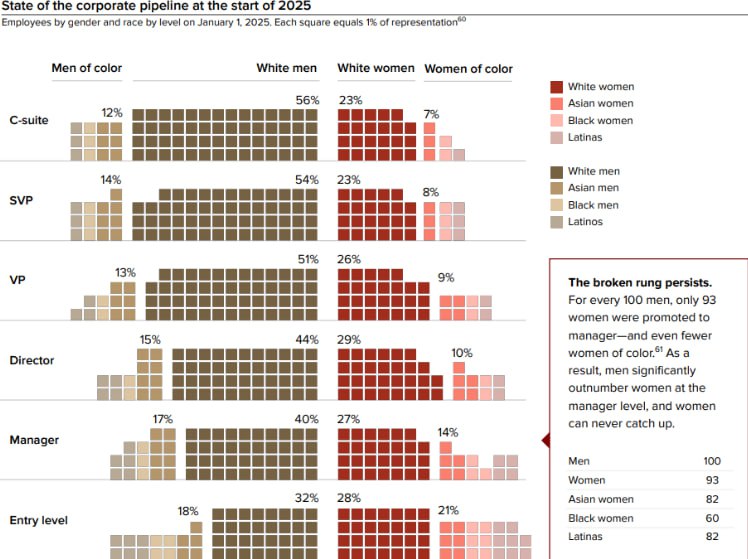

For the 11th year in a row, women remain underrepresented at every stage of the corporate ladder. Progress at the top has stopped as women hold just 29% of C-suite roles, the same as in 2024. This shows that the system ceased adjusting.

That kind of stagnation matters because the pipeline compounds. Small gaps at the entry-to-manager step do not stay small. They turn into a narrower leadership pool years later, long before formal succession planning even begins.

The McKinsey data points to one pressure point with unusual clarity — the first promotion to manager, often called the “broken rung.” It means that for every 100 men promoted to manager, only 93 women advance. For women of color, this issue is even wider, with only 60 women promoted per 100 men.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 18.

From there, we can confidently say that early promotion decisions shape who gets people-management experience and who builds leadership credibility. When access to high-visibility projects, stretch assignments, or senior advocates is uneven, promotion outcomes follow the same route.

That’s why we treat the broken rung as a governance issue. Unless early promotions are managed as a controlled process, upper-level representation will stay static. That’s regardless of how often companies declare gender equity a priority.

Career Support Is the Missing Layer

If the broken rung explains where women fall behind, career support explains why the gap persists.

Apart from performance, progression hinges on who gets sponsored, backed, and placed in the view of decision-makers. That’s where the system starts to diverge. Across levels, women receive less of this support. And this difference is sharpest early on, when trajectories are being shaped.

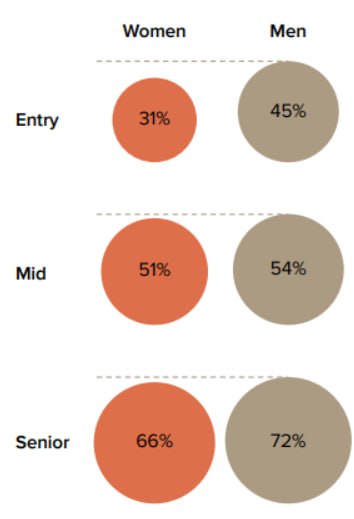

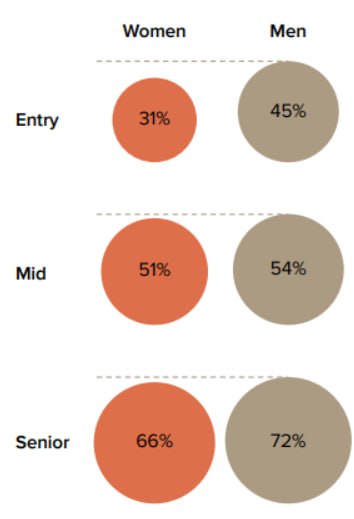

Sponsorship accelerates careers

According to Women in the Workplace 2025, employees with sponsors are nearly twice as likely to be promoted. Yet just 31% of entry-level women report having a sponsor, compared to 45% of men. Fewer still have senior or multiple sponsors — the type that influence visibility and buffer against loss in promotion reviews.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 5.

This matters because sponsorships aren't about soft guidance alone. Sponsors recommend, defend, and assign risk-weighted opportunities. So when sponsorship stays informal, it moves along familiar lines — those already inside the network. That’s how inertia manifests itself.

Manager engagement defines outcomes

Direct managers shape career movement more than any formal policy. They allocate stretch assignments, frame performance for review cycles, and signal who’s seen as ready for more. However, data show women are less likely than men to report that their manager supports their advancement. That’s especially true when it comes to lateral role changes, cross-functional shifts, or risk-based visibility.

We think it primarily stems from managerial drift, where project delivery is prioritized, but talent navigation is not. In that vacuum, bias gets operationalized. People are advanced based on comfort, proximity, or assumed fit — all of which strengthen underrepresentation over time.

Changing outcomes requires governing manager behaviour. Career advocacy only matters if it’s measured, so it has to become a tracked function.

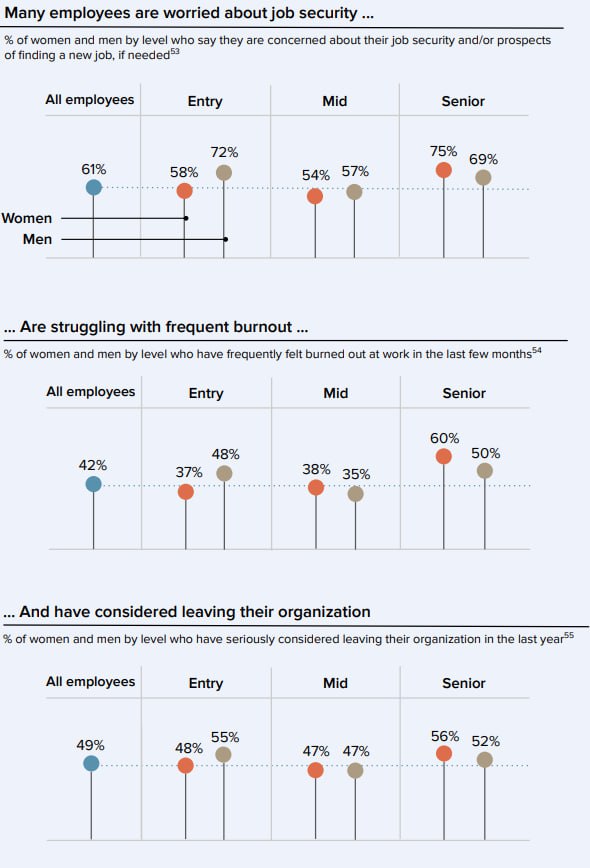

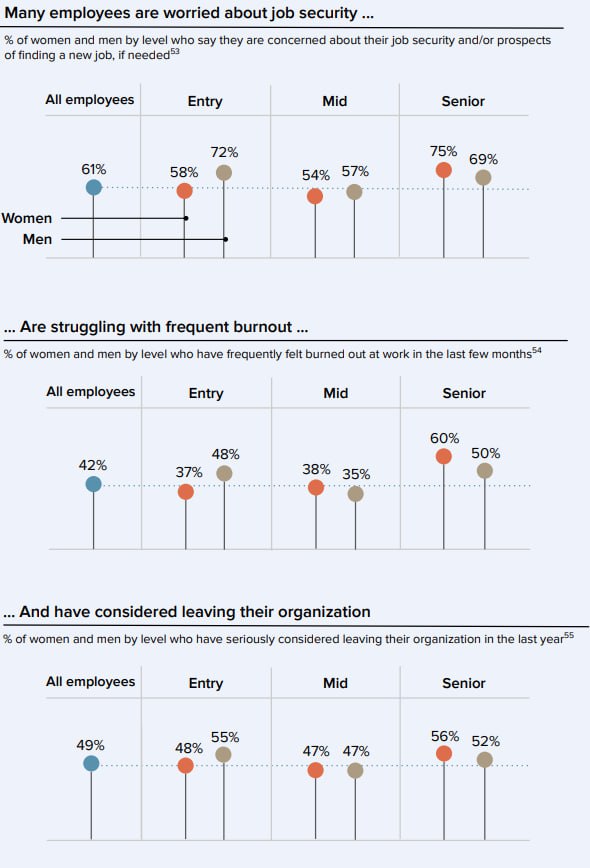

Burnout, Retention Risk, and Leadership Sustainability

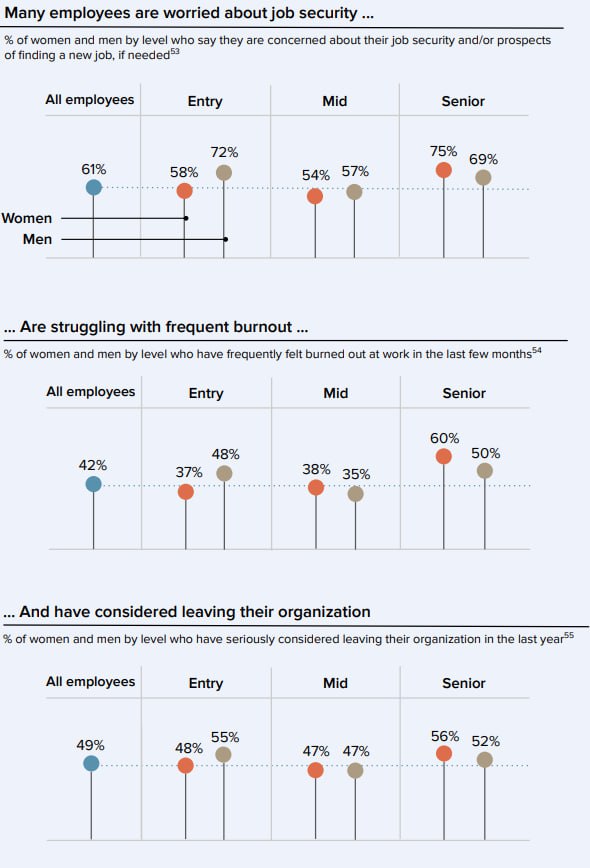

One of the most concerning findings in Women in the Workplace 2025 is how women experience senior roles once they reach them. Burnout and job insecurity are primarily concentrated among senior women, particularly those who have recently stepped into leadership positions.

Senior-level women with five years or less at their company report markedly higher levels of strain. Seven in ten say they frequently feel burned out, while more than eight in ten worry about job security. For Black women, these pressures are even higher, with less protection in how their performance is defended.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 16.

This underscores how leadership roles are structured and judged. Senior women are expected to manage complexity, drive change, and represent progress at once. They work under tighter scrutiny and a narrower room for error. So when that pressure is not matched by authority, resourcing, or sponsorship, the role becomes fragile.

We see this as a retention risk. Persistent burnout means that senior jobs are still shaped by informal protection. Reputation, alliances, and proximity continue to determine how long women stay and how far they move. Many remain in the role longer than expected, but fewer seek the next step. They stay visible without moving forward.

Over time, this breaks the illusion of progress. Representation may look steady, but the system beneath is still eroding. Until senior roles are designed to be sustainable, with clear authority, real backing, and space to grow, advancement will remain unstable.

What Actually Shapes Women’s Leadership in 2026

Most corporate equity frameworks describe intent. Yet, we’re more interested in outcomes, as leadership paths form through systems. These systems have few moving parts: who gets early selection, who becomes eligible to decision-makers, who is allowed to take risk, and who exits without return.

In our view, these five mechanics below will define the shape of women’s leadership in finance, tech, and communications in 2026.

Early selection defines who gets access

In fact, leadership starts when someone decides you’re “ready” and gives you real responsibility. In fintech and other industries, that usually means ownership over money, clients, or decisions.

Once someone gets that trust, others start to follow. That’s how a person enters the leadership track. If they don’t get picked early, they usually don’t get picked later. Most companies don’t revisit people they passed over, so they don’t ask who was missed.

A woman who didn’t get the first big promotion is seen as a solid performer, but not someone to bet on. She gets safe roles, and nothing in the system tells decision-makers to reconsider. That’s how careers stop moving — through silence.

Visibility must still be manually earned

Good work matters. But it has to be explained, placed in context, and made visible to the right people. That still depends on who notices, who speaks up, and who connects your results to bigger goals.

Even in firms with clear metrics, women say their impact often stays invisible until someone brings it into the conversation. When no one explains your value, you get left out of the next round of decisions.

As Eugenia Mykuliak, CEO of B2PRIME, said in her Women Leading the Way interview: “As a woman, I often had to put extra effort into proving my competence again and again before being taken seriously.”

Until companies stop relying on individuals to push their way into visibility, it will always benefit those who were already known.

Managers control more than they realise

Managers often don’t think of themselves as part of the leadership pipeline, as their job is to deliver results. They don’t always see that the way they assign work, give feedback, and frame people’s performance decides who moves forward.

If a manager doesn’t speak up for someone, that person stalls. No one else steps in. In hybrid teams, it matters even more. Women who work remotely are easy to overlook when presence is still confused with commitment.

When someone is doing well but no one is positioning them for more, they get stuck. That’s a lack of signal. Managers might think they’re being fair by staying neutral. In reality, they’re letting bias run on autopilot.

Access to risk still follows comfort

People grow when they take on real risk. That usually means launching something new, taking over a failing area, or representing the company publicly. These chances are often given to people who already look like leaders.

That’s how trust gets recycled. The people who are already known get the opportunities that lead to growth. The ones who haven’t been tested are told to wait.

Many women get stuck doing stabilising work. It matters, but it doesn’t build upward momentum. Meanwhile, the roles that carry risk and visibility keep going to people who are familiar, easy to back, or seen as a “safe bet.”

To change that, companies have to stop assigning risk based on comfort. Otherwise, women will keep proving themselves in roles that don’t lead anywhere.

Exit often reflects design failure

It’s easy to say women leave because of burnout. It’s harder to ask whether the roles they left were ever set up to support them.

In senior positions, we still see the same problems: high pressure, unclear authority, and constant visibility with little protection. If a woman joins from the outside, she often doesn’t have the safety net that her male peers do.

If women keep leaving after being promoted, then the system is working exactly as designed — it promotes them, pressures them, and then loses them. Yet it was never built to keep them.

Leadership needs to be something people can stay in. That means giving real authority, clear support, and a fair margin for error. Without that, we’ll keep seeing the same exits, no matter how many women get promoted.

Conclusion

In 2026, we believe women’s advancement will depend less on stated priorities and more on how career movement is designed behind the scenes. The Women in the Workplace 2025 report highlighted that outcomes follow structure. When promotions, sponsorship, and leadership roles are managed informally, progress slows. When they’re governed deliberately, it holds.

At Drofa Comms, we treat this report as a baseline because it quantifies the cost of leaving systems unstructured. Across finance, tech, and communications, we’ve seen how early promotion, managed visibility, and deliberate sponsorship shape real careers.

Advancement depends on whether organisations are willing to act on that insight through decisions. The companies that embed structure into how they identify, trust, and retain talent will keep expanding their leadership pipelines. Those who treat it as a messaging issue won’t.

In 2025, the discussion around women’s advancement stayed loud and visible. Yet promotion and leadership representation often do not move in practice. This is exactly what Women in the Workplace 2025, published by McKinsey & Company in partnership with LeanIn.Org, examines.

The report compiles more than a decade of longitudinal data and shows where progress holds, where it stalls, and where it starts to reverse. According to it, only 50% of companies now say that advancing women’s careers is a top priority, down from 65% in 2019. Nearly half of women report lower interest in promotion than earlier in their careers. That’s even when performance ratings match or exceed those of male peers.

At Drofa Comms, we observe the same patterns in finance and technology. These sectors operate with tighter risk tolerance and stronger internal gatekeeping. Promotion windows can be narrow, while endorsement can outweigh effort. This is also where communications becomes part of the operating system. Visibility is built through staffing, access to decision-makers, and the narrative carried into calibration.

We treat this report as a baseline. Below, let’s unpack the key findings through a practical lens on visibility and women’s leadership in 2026.

The Leadership Pipeline Gap and What’s Driving It

For the 11th year in a row, women remain underrepresented at every stage of the corporate ladder. Progress at the top has stopped as women hold just 29% of C-suite roles, the same as in 2024. This shows that the system ceased adjusting.

That kind of stagnation matters because the pipeline compounds. Small gaps at the entry-to-manager step do not stay small. They turn into a narrower leadership pool years later, long before formal succession planning even begins.

The McKinsey data points to one pressure point with unusual clarity — the first promotion to manager, often called the “broken rung.” It means that for every 100 men promoted to manager, only 93 women advance. For women of color, this issue is even wider, with only 60 women promoted per 100 men.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 18.

From there, we can confidently say that early promotion decisions shape who gets people-management experience and who builds leadership credibility. When access to high-visibility projects, stretch assignments, or senior advocates is uneven, promotion outcomes follow the same route.

That’s why we treat the broken rung as a governance issue. Unless early promotions are managed as a controlled process, upper-level representation will stay static. That’s regardless of how often companies declare gender equity a priority.

Career Support Is the Missing Layer

If the broken rung explains where women fall behind, career support explains why the gap persists.

Apart from performance, progression hinges on who gets sponsored, backed, and placed in the view of decision-makers. That’s where the system starts to diverge. Across levels, women receive less of this support. And this difference is sharpest early on, when trajectories are being shaped.

Sponsorship accelerates careers

According to Women in the Workplace 2025, employees with sponsors are nearly twice as likely to be promoted. Yet just 31% of entry-level women report having a sponsor, compared to 45% of men. Fewer still have senior or multiple sponsors — the type that influence visibility and buffer against loss in promotion reviews.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 5.

This matters because sponsorships aren't about soft guidance alone. Sponsors recommend, defend, and assign risk-weighted opportunities. So when sponsorship stays informal, it moves along familiar lines — those already inside the network. That’s how inertia manifests itself.

Manager engagement defines outcomes

Direct managers shape career movement more than any formal policy. They allocate stretch assignments, frame performance for review cycles, and signal who’s seen as ready for more. However, data show women are less likely than men to report that their manager supports their advancement. That’s especially true when it comes to lateral role changes, cross-functional shifts, or risk-based visibility.

We think it primarily stems from managerial drift, where project delivery is prioritized, but talent navigation is not. In that vacuum, bias gets operationalized. People are advanced based on comfort, proximity, or assumed fit — all of which strengthen underrepresentation over time.

Changing outcomes requires governing manager behaviour. Career advocacy only matters if it’s measured, so it has to become a tracked function.

Burnout, Retention Risk, and Leadership Sustainability

One of the most concerning findings in Women in the Workplace 2025 is how women experience senior roles once they reach them. Burnout and job insecurity are primarily concentrated among senior women, particularly those who have recently stepped into leadership positions.

Senior-level women with five years or less at their company report markedly higher levels of strain. Seven in ten say they frequently feel burned out, while more than eight in ten worry about job security. For Black women, these pressures are even higher, with less protection in how their performance is defended.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 16.

This underscores how leadership roles are structured and judged. Senior women are expected to manage complexity, drive change, and represent progress at once. They work under tighter scrutiny and a narrower room for error. So when that pressure is not matched by authority, resourcing, or sponsorship, the role becomes fragile.

We see this as a retention risk. Persistent burnout means that senior jobs are still shaped by informal protection. Reputation, alliances, and proximity continue to determine how long women stay and how far they move. Many remain in the role longer than expected, but fewer seek the next step. They stay visible without moving forward.

Over time, this breaks the illusion of progress. Representation may look steady, but the system beneath is still eroding. Until senior roles are designed to be sustainable, with clear authority, real backing, and space to grow, advancement will remain unstable.

What Actually Shapes Women’s Leadership in 2026

Most corporate equity frameworks describe intent. Yet, we’re more interested in outcomes, as leadership paths form through systems. These systems have few moving parts: who gets early selection, who becomes eligible to decision-makers, who is allowed to take risk, and who exits without return.

In our view, these five mechanics below will define the shape of women’s leadership in finance, tech, and communications in 2026.

Early selection defines who gets access

In fact, leadership starts when someone decides you’re “ready” and gives you real responsibility. In fintech and other industries, that usually means ownership over money, clients, or decisions.

Once someone gets that trust, others start to follow. That’s how a person enters the leadership track. If they don’t get picked early, they usually don’t get picked later. Most companies don’t revisit people they passed over, so they don’t ask who was missed.

A woman who didn’t get the first big promotion is seen as a solid performer, but not someone to bet on. She gets safe roles, and nothing in the system tells decision-makers to reconsider. That’s how careers stop moving — through silence.

Visibility must still be manually earned

Good work matters. But it has to be explained, placed in context, and made visible to the right people. That still depends on who notices, who speaks up, and who connects your results to bigger goals.

Even in firms with clear metrics, women say their impact often stays invisible until someone brings it into the conversation. When no one explains your value, you get left out of the next round of decisions.

As Eugenia Mykuliak, CEO of B2PRIME, said in her Women Leading the Way interview: “As a woman, I often had to put extra effort into proving my competence again and again before being taken seriously.”

Until companies stop relying on individuals to push their way into visibility, it will always benefit those who were already known.

Managers control more than they realise

Managers often don’t think of themselves as part of the leadership pipeline, as their job is to deliver results. They don’t always see that the way they assign work, give feedback, and frame people’s performance decides who moves forward.

If a manager doesn’t speak up for someone, that person stalls. No one else steps in. In hybrid teams, it matters even more. Women who work remotely are easy to overlook when presence is still confused with commitment.

When someone is doing well but no one is positioning them for more, they get stuck. That’s a lack of signal. Managers might think they’re being fair by staying neutral. In reality, they’re letting bias run on autopilot.

Access to risk still follows comfort

People grow when they take on real risk. That usually means launching something new, taking over a failing area, or representing the company publicly. These chances are often given to people who already look like leaders.

That’s how trust gets recycled. The people who are already known get the opportunities that lead to growth. The ones who haven’t been tested are told to wait.

Many women get stuck doing stabilising work. It matters, but it doesn’t build upward momentum. Meanwhile, the roles that carry risk and visibility keep going to people who are familiar, easy to back, or seen as a “safe bet.”

To change that, companies have to stop assigning risk based on comfort. Otherwise, women will keep proving themselves in roles that don’t lead anywhere.

Exit often reflects design failure

It’s easy to say women leave because of burnout. It’s harder to ask whether the roles they left were ever set up to support them.

In senior positions, we still see the same problems: high pressure, unclear authority, and constant visibility with little protection. If a woman joins from the outside, she often doesn’t have the safety net that her male peers do.

If women keep leaving after being promoted, then the system is working exactly as designed — it promotes them, pressures them, and then loses them. Yet it was never built to keep them.

Leadership needs to be something people can stay in. That means giving real authority, clear support, and a fair margin for error. Without that, we’ll keep seeing the same exits, no matter how many women get promoted.

Conclusion

In 2026, we believe women’s advancement will depend less on stated priorities and more on how career movement is designed behind the scenes. The Women in the Workplace 2025 report highlighted that outcomes follow structure. When promotions, sponsorship, and leadership roles are managed informally, progress slows. When they’re governed deliberately, it holds.

At Drofa Comms, we treat this report as a baseline because it quantifies the cost of leaving systems unstructured. Across finance, tech, and communications, we’ve seen how early promotion, managed visibility, and deliberate sponsorship shape real careers.

Advancement depends on whether organisations are willing to act on that insight through decisions. The companies that embed structure into how they identify, trust, and retain talent will keep expanding their leadership pipelines. Those who treat it as a messaging issue won’t.

In 2025, the discussion around women’s advancement stayed loud and visible. Yet promotion and leadership representation often do not move in practice. This is exactly what Women in the Workplace 2025, published by McKinsey & Company in partnership with LeanIn.Org, examines.

The report compiles more than a decade of longitudinal data and shows where progress holds, where it stalls, and where it starts to reverse. According to it, only 50% of companies now say that advancing women’s careers is a top priority, down from 65% in 2019. Nearly half of women report lower interest in promotion than earlier in their careers. That’s even when performance ratings match or exceed those of male peers.

At Drofa Comms, we observe the same patterns in finance and technology. These sectors operate with tighter risk tolerance and stronger internal gatekeeping. Promotion windows can be narrow, while endorsement can outweigh effort. This is also where communications becomes part of the operating system. Visibility is built through staffing, access to decision-makers, and the narrative carried into calibration.

We treat this report as a baseline. Below, let’s unpack the key findings through a practical lens on visibility and women’s leadership in 2026.

The Leadership Pipeline Gap and What’s Driving It

For the 11th year in a row, women remain underrepresented at every stage of the corporate ladder. Progress at the top has stopped as women hold just 29% of C-suite roles, the same as in 2024. This shows that the system ceased adjusting.

That kind of stagnation matters because the pipeline compounds. Small gaps at the entry-to-manager step do not stay small. They turn into a narrower leadership pool years later, long before formal succession planning even begins.

The McKinsey data points to one pressure point with unusual clarity — the first promotion to manager, often called the “broken rung.” It means that for every 100 men promoted to manager, only 93 women advance. For women of color, this issue is even wider, with only 60 women promoted per 100 men.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 18.

From there, we can confidently say that early promotion decisions shape who gets people-management experience and who builds leadership credibility. When access to high-visibility projects, stretch assignments, or senior advocates is uneven, promotion outcomes follow the same route.

That’s why we treat the broken rung as a governance issue. Unless early promotions are managed as a controlled process, upper-level representation will stay static. That’s regardless of how often companies declare gender equity a priority.

Career Support Is the Missing Layer

If the broken rung explains where women fall behind, career support explains why the gap persists.

Apart from performance, progression hinges on who gets sponsored, backed, and placed in the view of decision-makers. That’s where the system starts to diverge. Across levels, women receive less of this support. And this difference is sharpest early on, when trajectories are being shaped.

Sponsorship accelerates careers

According to Women in the Workplace 2025, employees with sponsors are nearly twice as likely to be promoted. Yet just 31% of entry-level women report having a sponsor, compared to 45% of men. Fewer still have senior or multiple sponsors — the type that influence visibility and buffer against loss in promotion reviews.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 5.

This matters because sponsorships aren't about soft guidance alone. Sponsors recommend, defend, and assign risk-weighted opportunities. So when sponsorship stays informal, it moves along familiar lines — those already inside the network. That’s how inertia manifests itself.

Manager engagement defines outcomes

Direct managers shape career movement more than any formal policy. They allocate stretch assignments, frame performance for review cycles, and signal who’s seen as ready for more. However, data show women are less likely than men to report that their manager supports their advancement. That’s especially true when it comes to lateral role changes, cross-functional shifts, or risk-based visibility.

We think it primarily stems from managerial drift, where project delivery is prioritized, but talent navigation is not. In that vacuum, bias gets operationalized. People are advanced based on comfort, proximity, or assumed fit — all of which strengthen underrepresentation over time.

Changing outcomes requires governing manager behaviour. Career advocacy only matters if it’s measured, so it has to become a tracked function.

Burnout, Retention Risk, and Leadership Sustainability

One of the most concerning findings in Women in the Workplace 2025 is how women experience senior roles once they reach them. Burnout and job insecurity are primarily concentrated among senior women, particularly those who have recently stepped into leadership positions.

Senior-level women with five years or less at their company report markedly higher levels of strain. Seven in ten say they frequently feel burned out, while more than eight in ten worry about job security. For Black women, these pressures are even higher, with less protection in how their performance is defended.

Source: McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org, Women in the Workplace 2025, page 16.

This underscores how leadership roles are structured and judged. Senior women are expected to manage complexity, drive change, and represent progress at once. They work under tighter scrutiny and a narrower room for error. So when that pressure is not matched by authority, resourcing, or sponsorship, the role becomes fragile.

We see this as a retention risk. Persistent burnout means that senior jobs are still shaped by informal protection. Reputation, alliances, and proximity continue to determine how long women stay and how far they move. Many remain in the role longer than expected, but fewer seek the next step. They stay visible without moving forward.

Over time, this breaks the illusion of progress. Representation may look steady, but the system beneath is still eroding. Until senior roles are designed to be sustainable, with clear authority, real backing, and space to grow, advancement will remain unstable.

What Actually Shapes Women’s Leadership in 2026

Most corporate equity frameworks describe intent. Yet, we’re more interested in outcomes, as leadership paths form through systems. These systems have few moving parts: who gets early selection, who becomes eligible to decision-makers, who is allowed to take risk, and who exits without return.

In our view, these five mechanics below will define the shape of women’s leadership in finance, tech, and communications in 2026.

Early selection defines who gets access

In fact, leadership starts when someone decides you’re “ready” and gives you real responsibility. In fintech and other industries, that usually means ownership over money, clients, or decisions.

Once someone gets that trust, others start to follow. That’s how a person enters the leadership track. If they don’t get picked early, they usually don’t get picked later. Most companies don’t revisit people they passed over, so they don’t ask who was missed.

A woman who didn’t get the first big promotion is seen as a solid performer, but not someone to bet on. She gets safe roles, and nothing in the system tells decision-makers to reconsider. That’s how careers stop moving — through silence.

Visibility must still be manually earned

Good work matters. But it has to be explained, placed in context, and made visible to the right people. That still depends on who notices, who speaks up, and who connects your results to bigger goals.

Even in firms with clear metrics, women say their impact often stays invisible until someone brings it into the conversation. When no one explains your value, you get left out of the next round of decisions.

As Eugenia Mykuliak, CEO of B2PRIME, said in her Women Leading the Way interview: “As a woman, I often had to put extra effort into proving my competence again and again before being taken seriously.”

Until companies stop relying on individuals to push their way into visibility, it will always benefit those who were already known.

Managers control more than they realise

Managers often don’t think of themselves as part of the leadership pipeline, as their job is to deliver results. They don’t always see that the way they assign work, give feedback, and frame people’s performance decides who moves forward.

If a manager doesn’t speak up for someone, that person stalls. No one else steps in. In hybrid teams, it matters even more. Women who work remotely are easy to overlook when presence is still confused with commitment.

When someone is doing well but no one is positioning them for more, they get stuck. That’s a lack of signal. Managers might think they’re being fair by staying neutral. In reality, they’re letting bias run on autopilot.

Access to risk still follows comfort

People grow when they take on real risk. That usually means launching something new, taking over a failing area, or representing the company publicly. These chances are often given to people who already look like leaders.

That’s how trust gets recycled. The people who are already known get the opportunities that lead to growth. The ones who haven’t been tested are told to wait.

Many women get stuck doing stabilising work. It matters, but it doesn’t build upward momentum. Meanwhile, the roles that carry risk and visibility keep going to people who are familiar, easy to back, or seen as a “safe bet.”

To change that, companies have to stop assigning risk based on comfort. Otherwise, women will keep proving themselves in roles that don’t lead anywhere.

Exit often reflects design failure

It’s easy to say women leave because of burnout. It’s harder to ask whether the roles they left were ever set up to support them.

In senior positions, we still see the same problems: high pressure, unclear authority, and constant visibility with little protection. If a woman joins from the outside, she often doesn’t have the safety net that her male peers do.

If women keep leaving after being promoted, then the system is working exactly as designed — it promotes them, pressures them, and then loses them. Yet it was never built to keep them.

Leadership needs to be something people can stay in. That means giving real authority, clear support, and a fair margin for error. Without that, we’ll keep seeing the same exits, no matter how many women get promoted.

Conclusion

In 2026, we believe women’s advancement will depend less on stated priorities and more on how career movement is designed behind the scenes. The Women in the Workplace 2025 report highlighted that outcomes follow structure. When promotions, sponsorship, and leadership roles are managed informally, progress slows. When they’re governed deliberately, it holds.

At Drofa Comms, we treat this report as a baseline because it quantifies the cost of leaving systems unstructured. Across finance, tech, and communications, we’ve seen how early promotion, managed visibility, and deliberate sponsorship shape real careers.

Advancement depends on whether organisations are willing to act on that insight through decisions. The companies that embed structure into how they identify, trust, and retain talent will keep expanding their leadership pipelines. Those who treat it as a messaging issue won’t.

London office

Rise, created by Barclays, 41 Luke St, London EC2A 4DP

Nicosia office

2043, Nikokreontos 29, office 202

DP FINANCE COMM LTD (#13523955) Registered Address: N1 7GU, 20-22 Wenlock Road, London, United Kingdom For Operations In The UK

AGAFIYA CONSULTING LTD (#HE 380737) Registered Address: 2043, Nikokreontos 29, Flat 202, Strovolos, Cyprus For Operations In The EU, LATAM, United Stated Of America And Provision Of Services Worldwide

Drofa © 2024

London office

Rise, created by Barclays, 41 Luke St, London EC2A 4DP

Nicosia office

2043, Nikokreontos 29, office 202

DP FINANCE COMM LTD (#13523955) Registered Address: N1 7GU, 20-22 Wenlock Road, London, United Kingdom For Operations In The UK

AGAFIYA CONSULTING LTD (#HE 380737) Registered Address: 2043, Nikokreontos 29, Flat 202, Strovolos, Cyprus For Operations In The EU, LATAM, United Stated Of America And Provision Of Services Worldwide

Drofa © 2024

London office

Rise, created by Barclays, 41 Luke St, London EC2A 4DP

Nicosia office

2043, Nikokreontos 29, office 202

DP FINANCE COMM LTD (#13523955) Registered Address: N1 7GU, 20-22 Wenlock Road, London, United Kingdom For Operations In The UK

AGAFIYA CONSULTING LTD (#HE 380737) Registered Address: 2043, Nikokreontos 29, Flat 202, Strovolos, Cyprus For Operations In The EU, LATAM, United Stated Of America And Provision Of Services Worldwide

Drofa © 2024